Vermont’s largest public transit provider is slashing service to avoid driving off a fiscal cliff. But will these cuts lead to a downward spiral, driving away the few remaining “choice riders” who take the bus? What alternatives are there to GMT trying to cut its way to financial stability? Read on for the latest in a series of articles analyzing problems and solutions in Vermont climate and land-use policy. If you like this article, please subscribe at the bottom.

(Photo by Flickr user Lunchbox Larry under a Creative Commons License).

Green Mountain Transit (GMT) has a lot going for it. It is the sole local public transit provider for much of Northwestern Vermont, a region that includes the state’s biggest city in Burlington and its flagship university and hospital. GMT’s vehicles serve as the only school buses for many of Burlington’s students, whose parents possess an abundance of the environmental ethic one would expect to translate into transit ridership. The state and region have adopted ambitious targets for cutting greenhouse gasses, and getting more people to take public transit more is one means of doing so. And Vermont spends an order of magnitude more per capita on public transit than other similarly small and rural states.

Yet GMT has been beset by well-publicized problems for years, including old equipment and, contrary to that green image, relatively low transit ridership. Now, GMT’s urban service area (Burlington and the other cities and towns that make up the populous core of Chittenden County) is facing a $2 million budget deficit for the fiscal year beginning July 2025. GMT is not unique in this: As of last year, nearly half of all surveyed transit agencies nationwide expected deficits by 2026. To save some funds against this shortfall, GMT announced it would start cutting service this December. The public officials, riders, and transit experts I talked to worry that this could lead to a negative feedback loop: driving the few remaining “choice riders” (those with another realistic mobility option) away from the bus, leading to lower fare collections and further service cuts down the road. When I asked Senator Thomas Chittenden, who has served on the Senate Transportation Committee and previously on GMT’s Board as a South Burlington City Councillor, whether he was concerned that the planned service reductions would lead to a negative feedback loop, he said bluntly, “We’re in it already.”

My questions when I set out to report this piece were first, how did we get here? And second, what could state and local officials do to head off such a downward spiral? As I found out, the answer to the first question is complicated. National economic trends and increasing costs are part of the answer. But GMT leaving money on the table, including by delaying a return to charging fares after providing fare-free service during the Covid-19 pandemic, and cutting administrative staff and marketing budgets probably are as well. As for the second question, although the state is doing a lot to fund transit, it has dragged its feet on implementing bold solutions, such as a dedicated source of funding for transit or disincentives to driving downtown. Clayton Clark, the General Manager of GMT, told me, “transit financing in Vermont is something that's been long recognized as something that needs improvement,” but that while there have been “a variety of studies, there hasn’t really been a whole lot of action.” Such choices could, in theory, lead to a virtuous upwards cycle of greater ridership and financial sustainability for GMT and the other transit agencies in Vermont.

As a caveat, I focused my reporting almost exclusively on Chittenden County, and even more particularly on the urban core around Burlington (including South Burlington, Williston, Winooski, and Essex Junction). I did so despite this being just part of GMT’s service area, because GMT’s urban territory deserves its own analysis. It is the only region dense enough to qualify as an urbanized area under federal definitions, and therefore, the only one with access to certain federal funds. Moreover, GMT tracks and reports the finances for its urban and rural service areas separately, and the urban area is where GMT is facing the current looming budget deficit. Rural public transit is also incredibly important but, as I learned, the dynamics there differ enough that reporting on those challenges would require a whole separate post.

Now, let’s take a ride.

How did we get here?

For the start of the story, let’s return to 2012, an unexpected high mark of transit ridership in the Burlington area. Chittenden County Transportation Authority (CCTA), the predecessor to GMT’s urban service, reported 2.75 million passenger trips that year. If you were one of those 2.75 million riders, you would have waited at most 15 minutes for the bus to show up on a busy route at rush hour; or at most 30 minutes outside of rush hour or on a less busy line. You paid $1.25 when you boarded for a one-way trip. You might have been taking the bus due to the high cost of gas—In New England, regular gas cost on average $3.71/gallon, while it stands at $3.05 today. And as the bus pulled away from the curb, the opening strains of “Little Talks” by Of Monsters and Men drifted out the window of a neighboring car.

From 2012 to 2019, bus ridership in Chittenden County gradually but inexorably declined while GMT’s costs increased. Predictably, GMT’s finances grew shakier (In 2016, CCTA formally merged into Green Mountain Transit, whose service area extends beyond Chittenden County). In an attempt to reverse this trend, GMT made several major changes in 2019: It replaced an ineffective bus-tracking app, eliminated deviations on urban routes, and changed service frequencies (also known as “headways”) to a uniform 20 minutes on some routes, and 30 minutes on others. These changes, it hoped, would improve the convenience and predictability of taking the bus while holding costs steady.

Of course, we all know what happened next. In a twist of fate certain to give social scientists heartburn, this natural experiment was derailed by a global pandemic. Not only did the Covid-19 lockdown make it difficult to measure the changes’ impact (although reporting at the time suggested that, if anything, ridership continued to fall through the end of 2019), it turned that ridership decline into a freefall. GMT’s urban ridership in Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 (which ran July 2020 – June 2021) was about half of what it was in FY 19, as illustrated by the graph below.

(Source: Data provided by Green Mountain Transit).

GMT (along with other Vermont transit agencies) stopped charging fares during the pandemic in 2020. I heard a couple of explanations for this change: both protecting drivers by lessening face-to-face interactions with passengers and easing a financial burden for transit users at a time many were struggling. The state legislature supported the change. To paper over the evaporation of fare revenue, which covered roughly 20% of GMT’s urban operating costs pre-pandemic, GMT used federal pandemic stimulus money, of which it received $17.8 million, and which it spent across several years. “Those COVID relief funds allowed us, for the last four years, to fill the gap between our income and expenses,” Clark told me.

GMT’s return to charging fares in May of 2024 came nearly a year later than intended. A recent report from GMT to the legislature blamed this in part on “an internal lack of communication” around the fact that some of GMT’s fareboxes had stopped working during their period of disuse.

Ridership has basically recovered on GMT’s urban (but not long-distance commuter) routes from the 2020 nadir, and fare-free service proved popular. Fares have now been reintroduced, but the cost increases that accelerated during the pandemic have not dissipated and federal stimulus funds have run dry. In other words, the bill has come due.

In response, GMT’s board has approved two rounds of service reductions, beginning this December. In the first round, GMT will trim night and weekend service on many urban routes and eliminate its least-utilized long-distance commuter route. In March, it will cut the number of daily trips on the commuter route between Montpelier and Burlington and consolidate the Milton and Saint Albans commuters. If these cuts do not shore up the budget, in May of 2025, GMT will begin to completely cut less-utilized local routes and lay off drivers, according to Clark.

I wanted to know what was going wrong for GMT before the pandemic. Sussing out what led ridership to fall from 2012 to 2019 proved difficult, though. A stronger economy and cheaper gas prices (both of which are globally associated with declines in public transit ridership) almost certainly played a role. And against the favorable conditions mentioned earlier, it’s worth noting a couple of unfavorable conditions GMT faces: Burlington, though a city, is a small and not very dense one. Vermont’s winter weather makes waiting for the bus a real pain in the toes. And Vermonters are used to driving long distances and the conveniences of car-ownership. Yet these factors were all present in 2012 as well.

One decision that, in hindsight, was probably a mistake was for CCTA and GMT to merge. When they did so, they formed one agency with responsibility for urban service in Chittenden County, rural service through much of Washington, Franklin, and Grand Isle Counties, and long-distance commuter service—but whose administrative staff did not increase commensurately. The merger (which started in 2011 before being formalized in 2016) presumably had the goal of improving efficiency and coordination, with the same managers able to oversee both fleets while the organization drew on the separate pools of federal funds available for rural and urban service. However, “there's no question that there's an increased level of difficulty with trying to manage both the urban system and a rural system,” Ross MacDonald, the Public Transit Program Manager at VTrans told me. Earlier this year, the legislature required GMT to study and report on whether transferring its rural and long-distance commuter operations to neighboring service providers would improve GMT’s financial outlook. GMT transmitted its consultant’s report to the legislature a little over a week ago, which found that in all but a couple of instances, it would. As GMT explained in its cover letter to the report: “GMT operates more service than it can effectively manage with its current staff size, and this has generated higher costs.” GMT will submit a second report in February with its own position on the consultant’s recommendation to transfer most rural service to other providers.

Additionally, at some point after 2012, GMT entered a negative feedback loop in response to a combination of decreased ridership and increased costs. It cut or delayed expenditures on repairing and replacing buses and fare-collection technology and cut administrative staff and marketing budgets, which likely hampered its ability to apply for competitive federal capital grants and attract choice riders. Sophia Donforth, a nonprofit director and public transit rider and advocate is one such rider, but said: “I and many people I know [already] do not ride the bus as much as I would like to because of the wait times and lack of reliability… It feels like the beginning of the end to me to make things less frequent and I’m worried about that.”

That’s the big picture. To get a more fine-grained portrait, I analyzed GMT budgets for the last 10 years (plus the projected budget for current fiscal year 2025). As we see in the graphs below, dramatic increases in key cost categories and stagnation or decline in some sources of revenue go a long way towards explaining GMT’s precarious financial situation.

Increasing Costs

Here are selected categories of GMT’s urban operating expenses for the past 10 years. These are not exhaustive, but rather the categories that my reporting led me to suspect might be most explanatory:

(Source: GMT Adjusted Operating Budgets 2015-2025, as Provided by GMT)

And here is the overall change in each cost category from 2015 to 2025:

*Changes are not adjusted for inflation, which was about 32% from 2015 to the present.

As the data show, GMT’s cost increases have largely been driven by the wages paid to drivers and mechanics, health insurance for employees, operating insurance, paratransit service provision, and vehicle parts. The largest absolute increase came in driver and mechanic wages and the largest percentage increase came in parts. Meanwhile, spending on marketing/public information and on fuel actually declined in this period.

Two caveats: First, these numbers are as reported, not adjusted for inflation. Adjusting for inflation, the amount spent on “other wages” actually declined, while increases in spending on driver and mechanic wages, health insurance, etc. were smaller than they appear above. Conversely, the reductions in spending on fuel and marketing expenses were greater than they appear above.

Second, these are just GMT’s operating expenses. There is a whole separate budget for capital expenses, such as purchasing new buses, installing new fare collection or other technologies, and fixing up bus stops. When capital expenditures lag behind the necessary levels to replace worn down equipment, operating expenses (including wages for mechanics and the cost of parts) tend to go up. GMT’s capital expense budget is largely funded by competitive federal grants that it must apply for, with a much smaller state and local component (about 80% federal, 20% state and local). Because GMT has slashed its administrative staff to the bone to close previous budget shortfalls, it is quite likely missing out on some of these competitive grants. “I definitely think that there's opportunities that we're missing because of staff capacity,” Clark told me, singling out microtransit in the Burlington area as something it has not had the capital funds to pursue. He also mentioned that roughly one third of GMT’s fixed-route fleet is older than the average lifespan for such heavy buses.

Revenues

What follows are the major sources of revenues raised by GMT over this same time period. Small sources such as advertising revenue are omitted, and directly apportioned federal funds are graphed separately, for ease of visualization:

(Source: GMT adjusted operating budgets 2015-2025, as provided by GMT. Note, until 2019, flexed federal funds were apparently included under “Other Federal/State Grants.” A request for confirmation from GMT was not replied to in time for publication)

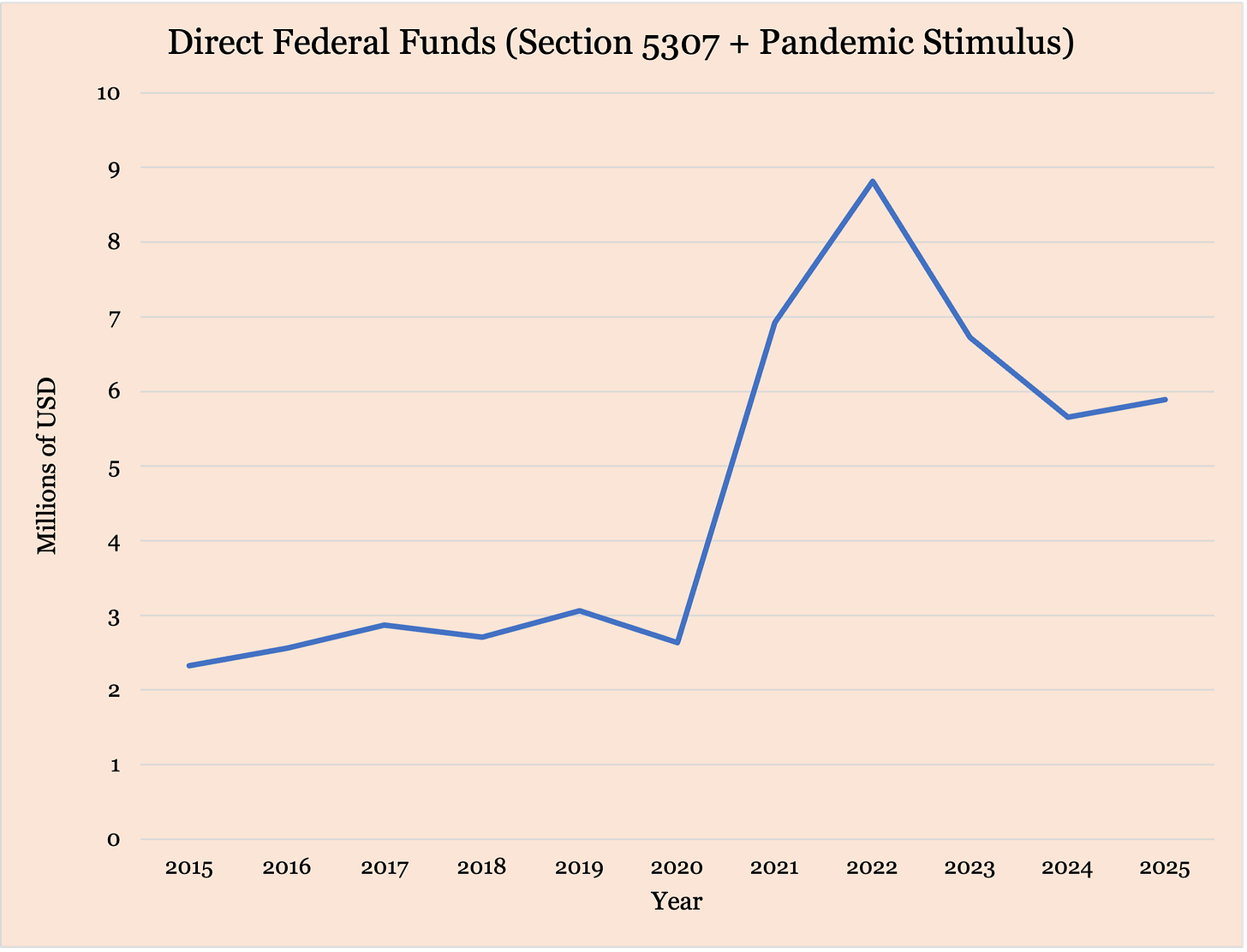

As the graphs above show, the main thing keeping GMT urban afloat in the face of increasing expenses has been a major increase in federal funds. These funds come in several forms. The first are directly appropriated to GMT under what’s known as the section 5307 program. GMT has received about $3-4 million annually from this program in recent years, and it takes into account both things over which GMT has no control (Burlington’s population and low-income population, for example), and things over which it does (percentage of the population riding transit and efficiency of service). The second category of federal funds are referred to as “flexed” funds, because they are appropriated to the state, which then decides how much to spend on different forms of transportation. The Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans) sends, or “flexes” a much larger share of these funds to public transit (and a comparatively smaller share to road projects) than other similarly small and rural states. However, both MacDonald from VTrans and Senator Andrew Perchlik told me they’ve seen increasing pressure to use more of this money on building and repairing roads and bridges, especially in the wake of devastating floods each of the past two years. The final main source of federal funds in recent years were one-time pandemic stimulus funds for which GMT, under the legal fiction of it being a municipality, was eligible. GMT received $17.8 million in such funds, which it spent across the past 5 fiscal years (these were not reported separately in the budgets GMT shared with me and show up in the “Direct Federal Funds” graph).

GMT has needed this influx of federal cash because its state and local funds and fare revenues have not kept pace with its growing expenses. GMT receives a large chunk of Transportation Fund money from the state legislature every year, referred to as its regular operating subsidy. This subsidy has largely remained flat, although the state has provided additional operating funds ranging from $600,000 to $1 million to GMT in recent years, which show up in “Other Federal/State Grants” above. For local funds, GMT is unique among Vermont transit agencies in that it is empowered by statute to raise revenue from the communities it serves, most of which are represented on GMT’s Board of Commissioners. There has been a delicate dance between GMT and these communities to come up with the formula that determines how much each will contribute, plus any special amounts over and above this. These municipal member assessments have grown an average of 3-4% per year in the past decade, roughly the pace of inflation. Lastly, fare revenues have plummeted since 2015. This category includes fares paid for paratransit service and money paid to GMT by the University of Vermont and Champlain College for unlimited rides for students and staff. Part of the reason fare revenues have not recovered is that the price per trip remains relatively low. Regular fares are at $2 for a one-way trip, up from $1.25 a decade ago. And long-distance commuter fares, which were $4 each way pre-pandemic, have actually decreased to $2. Fares for riders using GMT’s payment app are capped at $4 per day and $50 per month and GMT charges lower fares to youth, people over 60 or on Medicare, and people eligible under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

There will likely be a new revenue category in the budgets going forward: GMT has just set up a nonprofit arm that, according to Clark, will be able to raise funds through both private donations and grants that the Agency would not otherwise be eligible for. Some portion of these funds will likely be available to subsidize operations.

Where do we go from here?

If falling ridership and skyrocketing costs got GMT in this hole, what will it take to dig out? How can GMT enter into a virtuous cycle of increasing ridership and improved finances instead of the negative feedback loop it is currently in? Predictably, there are many ideas. What follows are four gleaned from published reports, interviews, and my own analysis. Several of these will be of interest outside of Chittenden County, because while GMT is the first Vermont transit operator post-pandemic to face such a deficit, others are close behind. Here are the four broad categories of solutions that surfaced through this reporting:

Stabilize and boost state funding levels via a dedicated funding source

Most of the state money Vermont sends to public transit comes from the Transportation Fund, which is funded mainly by taxes on gasoline and Department of Motor Vehicles fees. As with federal “flex” funds, public transit must compete with state highway construction and maintenance for this money and go through the uncertainty of annual appropriations, which has motivated the search for an additional and dedicated source of funding for public transit. It seems unlikely there will be an appetite for raising the gas tax (whose burden falls more heavily on low-income people) significantly. The Vermont Public Transportation Association (a membership group for the eight state transit agencies) therefore studied and proposed several new or enhanced sources of funding in a report it transmitted to the legislature this past January. The four ideas the VPTA ultimately recommended were:

Changing vehicle registration fees from flat fees to a percentage of the vehicle’s value (calculated to raise more revenue and be more of a progressive fee)

Imposing a small additional fee on all electric utility customers in the state

Charging a fee on retail delivery services like Amazon

Increasing the rental car tax

Both Senator Chittenden and Senator Perchlik, who also served on the Senate Transportation Committee in recent years, said they opposed the idea of an electric utility fee, which taxes a product that, for most users, is unrelated to transit behavior. They signaled openness to the other ideas, however. Senator Chittenden expressed support for the “ad valorem” vehicle registration fee, while Senator Perchlik said that the retail delivery charge was intriguing. These ideas would require the buy-in of legislators outside the transportation committees in both chambers of the legislature.

Disincentivize driving, to push more people onto public transit.

“If you want people to take the bus, you need to change the economic calculus to make it more attractive to do so,” Senator Chittenden told me. Other than making it more convenient or cheaper to take GMT’s urban buses, the main way to do this would be to make car ownership and driving more expensive or less convenient. That is not something that has ever really been attempted in Vermont. Senator Chittenden mentioned two major ideas he has for doing this: increasing the gas tax (though he admitted this was almost certainly dead on arrival from a political perspective) and taxing private parking that is not covered with solar panels. One related but different idea would be to encourage or require municipalities to charge a minimum amount for public parking in their downtown areas. Parking currently costs about $1/hr in downtown Burlington and is free in the new urban core of Market Street in South Burlington. Disincentives are predictably politically unpopular (and one can imagine businesses opposing anything that might deter already leery customers from making the trip downtown). Pairing such disincentives with improvements to and incentives to take transit would almost certainly be necessary to gain support for this option.

Find cheaper ways of providing transit service, chiefly micro-transit

“What I’d like to see [GMT] try is providing some of [the service it’s now having to cut] but on a cheaper cost per passenger basis—can they have smaller buses, for example—and can on-demand or micro-transit help bring down the cost per ride?” Senator Perchlik said.

Microtransit typically refers to anything smaller than a fixed-route bus: everything from a “cut-away” van of the sort you’d take from a car-rental agency to the airport, down to a minivan. “On-demand” refers to a model where riders can hail a ride from wherever they choose rather than waiting at a bus stop. GMT has piloted an on-demand mictrotransit model in the Montpelier area. Called “MyRide,” it has drawn mixed reviews. Some appreciate the convenience of the vans coming to their doorstep and lower emissions than traditional buses, while others lament the long wait and transit times as the vans make many disconnected stops. Sophia Donforth, who lives in Burlington but commutes to Montpelier on GMT’s commuter bus, said she has used MyRide to get from the Montpelier Transit center to her office, but it “doesn’t often come in a time frame that allows me to get very much time at work.”

There has not been a similar generally available microtransit program in the Burlington area, but that may be set to change. GMT currently contracts with the nonprofit Special Services Transportation Agency (SSTA) to provide on-demand microtransit, but only to the elderly and persons with disabilities. Clark told me, however, that GMT plans to study whether to ask SSTA to begin providing on-demand microtransit open to the general public at certain times and/or along certain routes.

The fly in this ointment is that microtransit might not actually be cheaper—or if it is, it is for reasons some would find objectionable. An early profile of the MyRide program found that it cost GMT more on a per-passenger basis than fixed-route buses pre-pandemic, principally due to low initial uptake (Those numbers flipped during the pandemic). And the main reason such service could be cheaper than fixed-route buses on an operating basis is that SSTA drivers are paid significantly less than GMT’s drivers. This is both because the SSTA drivers are not required to have a Commercial Driver’s License and because they are not unionized.

Encourage GMT to Act more like a Business

Finally, there are certain ways in which GMT is not currently acting with the level of self-interest one would expect from a business and could be encouraged to do so. This last is my own observation based on several data points, although it is in line with the conditions the Legislature imposed on its most recent disbursement of funds to GMT.

First, GMT currently charges the University of Vermont about $375,000 per year for unlimited rides for its staff and students, and Champlain College about $40,000 per year for the same, according to Clark. Looking just at UVM, this number appears quite low. Using UVM’s reported numbers for full time students as well as faculty and staff, this works out to just under $21 per person per year. There is certainly some imprecision in that calculation, since some of the students and staff might be ineligible for unlimited access under UVM policies, and of those eligible, clearly not all will use the service. Still, even if we divide the number of users in half, that amounts to a payment of $42 per person per year—less than what GMT now charges a regular user for the equivalent of a monthly bus pass. This seems like a large subsidy to this (relatively wealthy) institution.

Second, GMT contracted with the city of Burlington to provide extra service for the solar eclipse this past April, including shuttling people between parking on the Route 127 Beltline and downtown. This was before GMT had resumed charging fares, yet Clark told me GMT did not charge Burlington anything to provide this additional service. 50,000 visitors reportedly descended on Burlington for the eclipse and many paid $30 per car for parking. This seems like a significant missed opportunity for GMT to access some of that new revenue.

Third, GMT has not returned to charging higher fares on its long-distance commuter routes. Pre-pandemic, these routes cost $4 compared to the $1.50 for local routes; now, both are $2. Granted, GMT is still trying to attract riders back to these routes. But the fact that riders have not returned is likely due to the new reality of work-from-home, and not the cost of the service, which, even at $8 round trip, would be less than most commuters spend on gas to drive a comparable distance.

Fourth, according to Clark, GMT has not explored asking Burlington (which owns the airport) or Beta Technologies, which abuts it, to contribute more in order to keep or expand bus service to the Burlington airport. Either entity would, presumably, have an interest in a convenient and green transit option between downtown Burlington and the airport, where spotty (and expensive) cab service is the main option for any traveler who can’t drive or get a ride.

Lastly, GMT has cut marketing expenditures over the past decade to next to nothing. The infrequent service and lack of connectivity are the main reasons people I spoke with gave for not taking the bus more—but it stands to reason that not even knowing about all the transit options is another deterrent.

There will be Trade-offs

Whatever GMT and state and local officials do to try to right the ship, it is certain that there will be some trade-offs. One tension to keep track of is how the option serves each of the two major goals for transit. Greg Rowangould, Director of the University of Vermont’s Transportation Research Center, said of these two goals: “One is providing mobility for people who lack or don’t want to use other forms of mobility. The other is reducing traffic congestion, pollution, and emissions—for this goal, you need to get choice riders.” And for that, he said, “transit needs to be competitive with their other option, meaning it has to be fast, convenient, and not too expensive.”

MacDonald from VTrans, told me in a discussion of making headways more frequent, “about 70%, up to 90% of everybody on a bus in Vermont is a ‘needs’ rider. They don't have the other options. So, you know, we really need to focus on the most vulnerable, the economically disadvantaged, first and foremost, and then consider those choice riders…” But making such choice riders an afterthought seems to be in large part what led to such fiscal unsustainability in the first place. “I think what we've seen is that we are not able to sustain a successful transit service if we don't have choice riders,” said Kati Gallagher, a staff member at the Vermont Natural Resources Council and coordinator of the Transportation 4 VT coalition.

What is certain, as GMT heard in feedback at public hearings when the cuts were proposed, is that the service reductions will make life harder for people who depend on the bus—and make the razor-thin margins by which choice riders decide to take the bus even thinner. Donforth, the nonprofit director and transit advocate, said that without knowing which departure times on the Montpelier LINK will be eliminated, it’s hard to say for sure how the cuts will impact her. Yet she predicts that she will need to leave home earlier in the morning and miss seeing her kids before they leave for school. Or, she added, she’s looking into carpooling.

Related Reading and Listening

Shaun Robinson, VTDigger, “Green Mountain Transit to Move Forward with Further Service Reductions” (Nov. 12, 2024)

Rachel Hellman, Seven Days, “Green Mountain Transit Proposes Major Service Cuts” (Aug. 27, 2024)

Sabine Poux (Brave Little State), Vermont Public, “Mind the gap: Transit in Chittenden County faces uncertain future” (May 23, 2024)

Molly Walsh, Seven Days, “Low Ridership, Legal Woes and Broken Fare Boxes Bedevil Green Mountain Transit” (Oct. 9, 2019)

Joseph Stromberg, Vox, “The Real Reason American Public Transit is Such a Disaster” (Aug. 10, 2015)